A New Deal for Quilts is both a book and exhibition. The book is lavishly illustrated with governmental photography and images of quilts, including many from the collection of publisher the International Quilt Museum, in association with the University of Nebraska Press. Order it here. Accompanying the book is an exhibition at IQM with the same name, guest-curated by Janneken, which showcases quilts made during the New Deal era, including a TVA quilt, a friendship quilt created by WPA work crews in Oklahoma, and some of the ubiquitous scrap quilts of the era. The exhibition runs October 6, 2023 – April 20, 2024 at the IQM at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

A New Deal for Quilts is both a book and exhibition. The book is lavishly illustrated with governmental photography and images of quilts, including many from the collection of publisher the International Quilt Museum, in association with the University of Nebraska Press. Order it here. Accompanying the book is an exhibition at IQM with the same name, guest-curated by Janneken, which showcases quilts made during the New Deal era, including a TVA quilt, a friendship quilt created by WPA work crews in Oklahoma, and some of the ubiquitous scrap quilts of the era. The exhibition runs October 6, 2023 – April 20, 2024 at the IQM at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

During the New Deal—the Roosevelt administration’s legislative response to the Depression—not only did quiltmakers create quilts on both an individual and collective level in response to the unemployment, displacement, and recovery efforts in the U.S., the government drew on the symbolic heft of quilts and quiltmaking in its relief and rebuilding projects. The federal government used quilts to communicate about its programs assisting the impoverished and values and behaviors individuals and families should employ to lift their families out of dire straits. I assert that federal programs—including the Farm Security Administration, the Works Progress Administration, the National Youth Administration, the Federal Arts Program, and the Tennessee Valley Authority—embraced quilts to demonstrate the efficacy of these programs, show women how they could contribute to their families’ betterment, and generate empathy for the plight of displaced and impoverished Americans.

Both the government and American quiltmakers symbolically drew on myths of colonial-era fortitude and self-sufficiency as a means of overcoming poverty. Quiltmakers during this era used quilts to express their frustrations with the downturn and to feel empowered, despite precarious financial positions. These ideas stemmed from the nostalgia-fueled Colonial Revival of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which celebrated a romanticized version of the experiences of colonial-era Americans, while altering the values with which Americans tried to live, as many looked longingly to the imagined simplicity of the pre-industrial past despite the rapidly modernizing society.

By the time the Roosevelt Administration began combatting the Great Depression, the quilt had become an emblem of how to lift one’s family out of poverty, piece by piece. Quilts had acquired this symbolic heft over the previous century, when Americans developed and perpetuated ideas about why women made quilts and what these objects meant. By the 1930s many Americans were looking longingly back to the colonial era, in search of the frugality and values that allowed Americans during earlier challenging times to persevere. These ideas stemmed from the nostalgia-fueled Colonial Revival of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which celebrated a romanticized version of colonial American life. For quilters, this was double inspiration—they could adapt the fashion of colonial style quilts while also adopting their perceived frugality. And for those of limited economic means, such thrift—even if inspired by romantic ideas of quiltmaking—made good sense. The ideals of colonial quilts that permeated mainstream society from the late 19th century through the 1930s were in fact imagined ones, reinforced with magazines and newspapers alike offering quilt patterns inspired by old-fashioned designs and companies sponsoring quiltmaking competitions.

By the time the Roosevelt Administration began combatting the Great Depression, the quilt had become an emblem of how to lift one’s family out of poverty, piece by piece. Quilts had acquired this symbolic heft over the previous century, when Americans developed and perpetuated ideas about why women made quilts and what these objects meant. By the 1930s many Americans were looking longingly back to the colonial era, in search of the frugality and values that allowed Americans during earlier challenging times to persevere. These ideas stemmed from the nostalgia-fueled Colonial Revival of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which celebrated a romanticized version of colonial American life. For quilters, this was double inspiration—they could adapt the fashion of colonial style quilts while also adopting their perceived frugality. And for those of limited economic means, such thrift—even if inspired by romantic ideas of quiltmaking—made good sense. The ideals of colonial quilts that permeated mainstream society from the late 19th century through the 1930s were in fact imagined ones, reinforced with magazines and newspapers alike offering quilt patterns inspired by old-fashioned designs and companies sponsoring quiltmaking competitions.

During the Great Depression, many women sought employment as primary breadwinners. Works Progress Administration (WPA) sewing rooms employed hundreds of thousands of women around the country, including many African American, immigrant, and illiterate women, some of whom helped make quilts that were used in relief projects; created for hospitals, orphanages, or other state institutions; or given as gifts to elected officials. These WPA projects could employ women without a husband or father supporting them. Sewing rooms trained women to make quilts, resulting in the production of tens of thousands of bedcovers, along with the garments and mattresses that comprised the bulk of their output. Handicraft projects instructed women in more specialized patchwork and appliqué techniques, among other skills like block printing and bookbinding. Although the WPA aspired for these programs to provide transferable job skills that women would be able to use in for profit industry, its greater achievement was in lifting morale and promoting mutual aid.

During the Great Depression, many women sought employment as primary breadwinners. Works Progress Administration (WPA) sewing rooms employed hundreds of thousands of women around the country, including many African American, immigrant, and illiterate women, some of whom helped make quilts that were used in relief projects; created for hospitals, orphanages, or other state institutions; or given as gifts to elected officials. These WPA projects could employ women without a husband or father supporting them. Sewing rooms trained women to make quilts, resulting in the production of tens of thousands of bedcovers, along with the garments and mattresses that comprised the bulk of their output. Handicraft projects instructed women in more specialized patchwork and appliqué techniques, among other skills like block printing and bookbinding. Although the WPA aspired for these programs to provide transferable job skills that women would be able to use in for profit industry, its greater achievement was in lifting morale and promoting mutual aid.

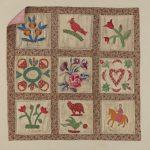

Out of work writers, artists, and other professionals found work in federal projects designed to document the past as a way of providing solace and inspiration in the present by looking to pre-industrial models of how to overcome hardships. The Index of American Design (IAD), part of the WPA’s Federal Art Project, employed artists to document traditional American arts with the aim of creating a record of American design that contemporary artists could draw upon. By the 1930s quilts were considered among the most quintessential of American objects, and the resulting IAD collection includes over 350 paintings of historical quilts. The WPA also sponsored the Federal Writers Project, which conducted interviews with African Americans who had grown up during slavery. It also collected interviews as part of the WPA Folklife Project, which documented the lives and traditional practices of Americans. Both sub-projects include interviews with women who recount quiltmaking. Looking to quilts as old-fashioned inspiration for “making do,” one geographic district of the Museum Extension Project, part of Pennsylvania’s WPA, created screenprinted quilt patterns based on historic quilts.

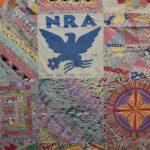

Out of work writers, artists, and other professionals found work in federal projects designed to document the past as a way of providing solace and inspiration in the present by looking to pre-industrial models of how to overcome hardships. The Index of American Design (IAD), part of the WPA’s Federal Art Project, employed artists to document traditional American arts with the aim of creating a record of American design that contemporary artists could draw upon. By the 1930s quilts were considered among the most quintessential of American objects, and the resulting IAD collection includes over 350 paintings of historical quilts. The WPA also sponsored the Federal Writers Project, which conducted interviews with African Americans who had grown up during slavery. It also collected interviews as part of the WPA Folklife Project, which documented the lives and traditional practices of Americans. Both sub-projects include interviews with women who recount quiltmaking. Looking to quilts as old-fashioned inspiration for “making do,” one geographic district of the Museum Extension Project, part of Pennsylvania’s WPA, created screenprinted quilt patterns based on historic quilts. Americans made hundreds of thousands of quilts during the Great Depression. While many are scrap quilts exhibiting signs of making do, and others use commercially available patterns inspired by the Colonial Revival, some makers constructed quilts with overt political messages, promoting New Deal programs, celebrating electoral victories, and depicting the Roosevelts. Quiltmakers crafted blue eagle National Recovery Act quilts, various Works Progress Administration quilts, and other quilts that demonstrated their allegiance to various New Deal programs.

Americans made hundreds of thousands of quilts during the Great Depression. While many are scrap quilts exhibiting signs of making do, and others use commercially available patterns inspired by the Colonial Revival, some makers constructed quilts with overt political messages, promoting New Deal programs, celebrating electoral victories, and depicting the Roosevelts. Quiltmakers crafted blue eagle National Recovery Act quilts, various Works Progress Administration quilts, and other quilts that demonstrated their allegiance to various New Deal programs.